By Thomas Naadi

In a big shop at the heart of the sprawling Makola market in Ghana’s capital, Accra, Nana Adwoa Enninful arranges rows of wigs.

The 59-year-old sells hair products and accessories from her shop.

Some of her business is carried out using mobile money, which is an electronic wallet service that allows registered users to store, send and receive payment using their accounts.

This payment method is faster, more convenient, and more reliable than the traditional banking system, according to Ms Enninful.

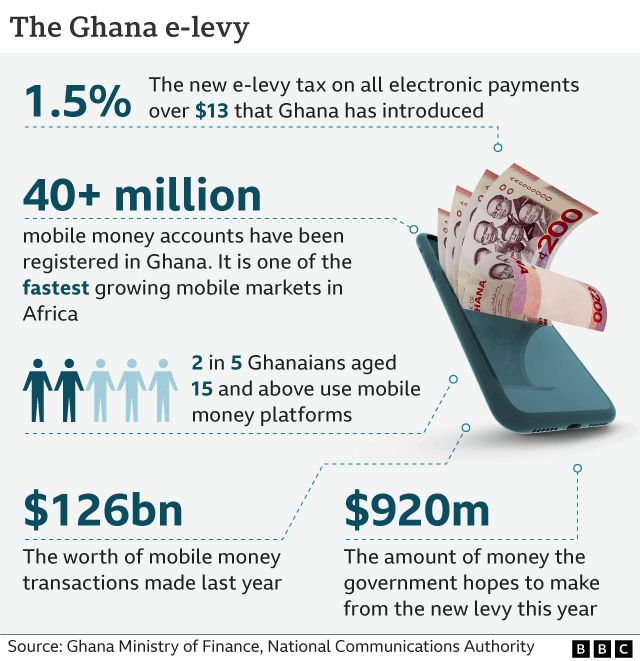

As a consequence, the government’s new 1.5% tax on all electronic transactions above 100 Ghanaian cedi ($13; £11) – known as the e-levy – is a source of concern for her. It comes into force on 1 May.

“We have to add e-levy on top of the cost of the item, which will increase the price,” she tells the BBC.

“Otherwise, we will go back to cash which sometimes doesn’t help us because we get fake notes and sometimes underpayments.”

Despite her measured reaction, telling me it is good the government is trying to raise money, she is still worried about the controversial tax, like many market sellers.

Ms Enninful is one of many market sellers worried about the controversial tax.

The e-levy will also apply to bank transfers and remittances as well as mobile money transactions.

Critics of the law say it will hit low-income workers and small businesses the hardest, as they rely heavily on mobile money transactions.

Last year, the parliamentary debate on the e-levy ended with punches being thrown, such was the level of disagreement. The law was eventually passed but only after opposition MPs staged a walkout.

Banks are far and few between in rural areas of the country and mobile payments are seen as a low-cost, safe and efficient alternative to either a bank account or holding large amounts of cash.

As a result nearly 40% of Ghanaians aged 15 and above use mobile money platforms.

But the e-levy has raised concerns over the future of mobile money.

There are already signs that people are turning their backs on electronic payments. The central bank has reported that the industry lost over $1bn in the two months from last November as consumers started using cash ahead of the tax coming into force.

The government has been trying to build a digital economy in recent years to reduce the use of physical cash. But it now admits the new tax could see a big drop in the use of mobile money services within the first few months of it taking effect.

Deputy Finance Minister John Kumah told local media that “there will be about 24% attrition rate in the three months to six months that we will introduce it”.

“The same research told us what should be done to bring back these people after a while, and we have all these things in place,” he said.

Much of Ghana’s economy operates outside the formal sector and less than 10% of the population pay direct taxes. The authorities have defended the new tax by saying that it will widen the tax base, boost government revenue and put a dent in the country’s $50bn debt.

In a recent interview with the BBC, Ghana’s President Nana Akufo Addo said that the country’s tax-to-GDP ratio was 13% – far lower than the average in West Africa of 18%. Most European countries have a ratio of 35-45%, while the US has about 25%.

“We are talking about taxing an industry where a lot of value is being created and we want to also bring that value into government coffers,” he added.

The government says it will use the money generated by the e-levy for development projects such as building roads and hospitals, and creating jobs to reduce unemployment, although some fear that the extra money raised could instead end up in the pockets of officials.

It is estimated that last year $126bn-worth of mobile money transactions were made and the government hopes that the e-levy will raise almost $1bn this financial year.

Some experts have suggested alternative ways to generate revenue.

Reworking existing taxes instead, like “corporate income tax, personal income tax, even VAT” could help the government raise even more money, professor Godfred Bokpin, a lecturer at the University of Ghana Business School, told the BBC.

Similar taxes introduced in Zimbabwe and Cameroon have also proved controversial.

In 2019, Zimbabwe introduced a 2% money transfer tax that was hugely unpopular. Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube agreed to review it but said it was too early to make adjustments as it was a major source of state revenue.

In Cameroon, a proposed 0.2% tax on mobile money transactions triggered a huge backlash and resulted in a social media campaign #EndMobileMoneyTax. The government still went ahead and implemented it in January this year.

Tanzania’s government is also now considering taxing online businesses. A team of experts from Meta – the company that owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp – visited the commercial hub of Dar es Salaam to hold talks with authorities on how to tax their services in the country.

It is likely that other African governments, reeling from the economic hardships of the Covid-19 pandemic and now facing the fallout from the Russia-Ukraine crisis, could turn to an e-levy to raise more money, despite the impact on some citizens.

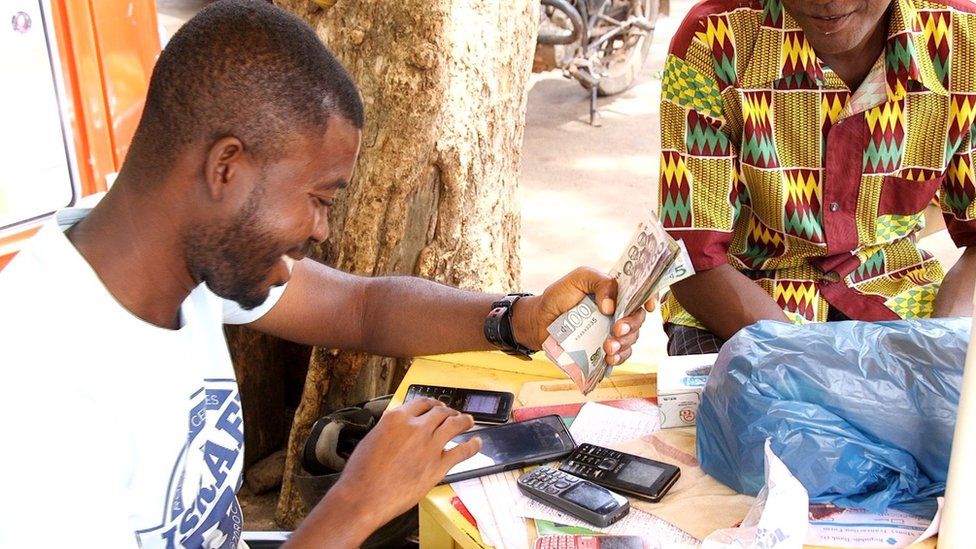

In Ghana, the thousands of people directly employed in the mobile money business are even more alarmed than the traders.

“I’m very worried about the e-levy. The government did not educate us the citizens well about it,” said James Mawuli, who works as a mobile money vendor in Accra.

The 32-year-old helps people manage their mobile money accounts and withdraw cash as needed. He said he had already lost many customers because of the planned e-levy and fears he might lose his job.

“A lot of people have even started withdrawing all their money ahead of its implementation and our transactions have reduced,” he said.

“It’s going to be a big problem for us.”

Opposition MPs are already challenging the legality of the law and have filed an injunction at the Supreme Court.

That ruling is expected in early May just days after the tax comes into effect.