In our series of letters from African journalists, Ismail Einashe goes for some tech lessons in Kenya.

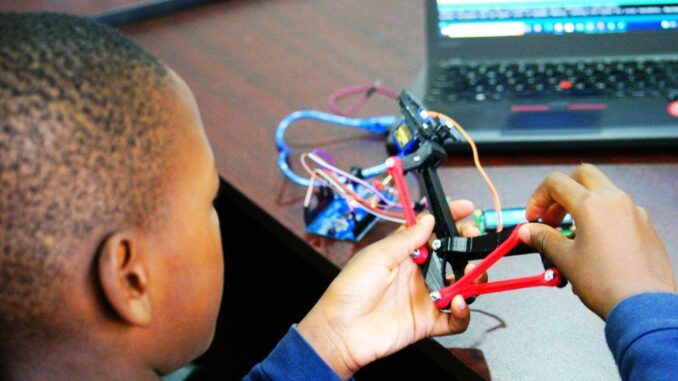

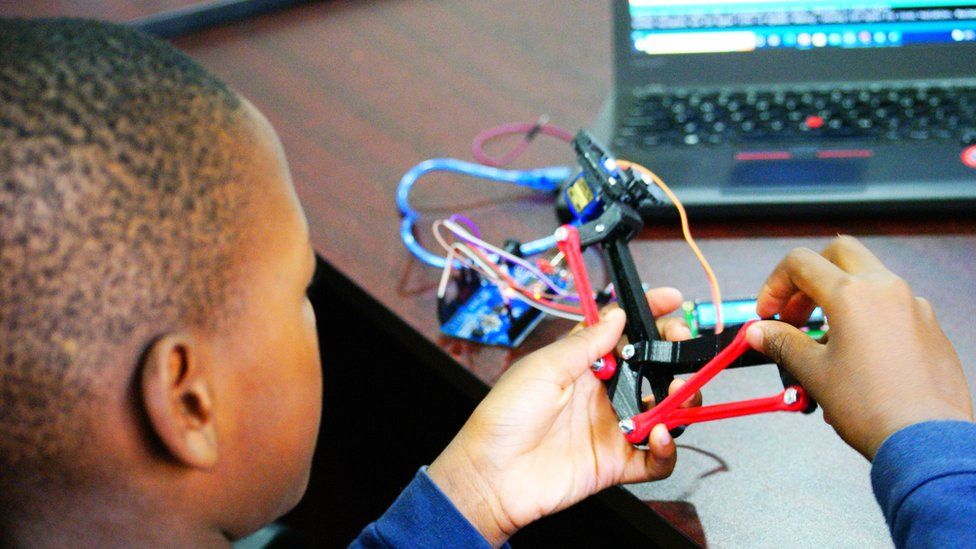

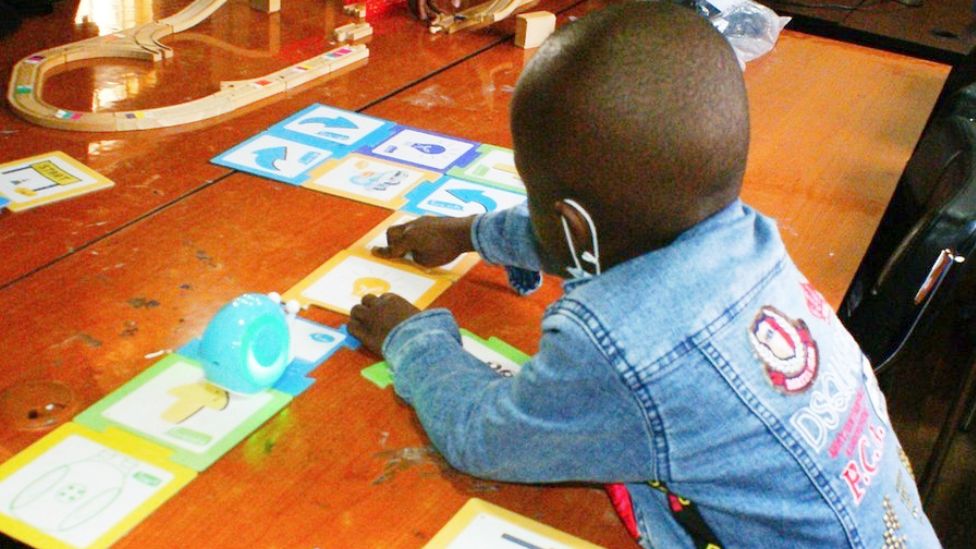

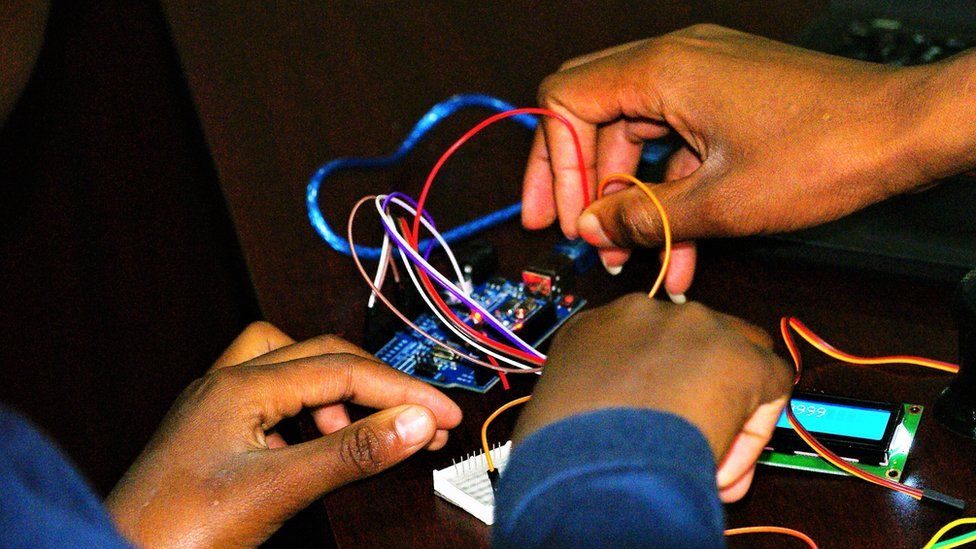

On a balmy morning in Nairobi a group of children are building robots using motors and wires, while in an adjacent room a child is learning how to use software to spell their name on a computer.

This hive of tech activity is taking place at the headquarters of the Stem Impact Centre, a two-story bungalow in the centre of the Kenyan capital.

Established in September 2020, the centre supports schools by providing their students with the space to learn coding and robotics and take a DIY approach to learning technology.

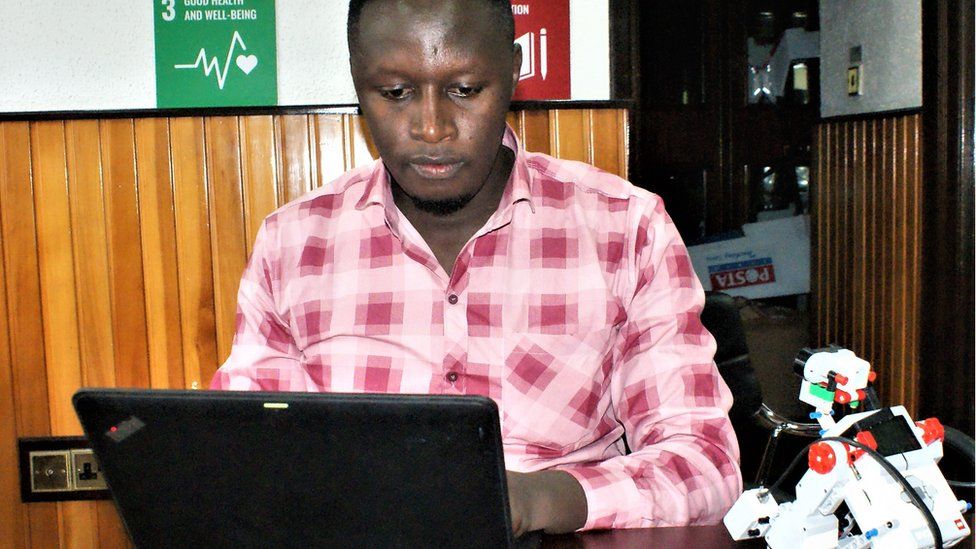

The centre is the brainchild of Alex Magu, who founded it driven by a passion to “democratise computer science” in Kenya.

He believes giving every child access to tech-based resources is vital for the development of Kenya.

And it seems that the Kenyan government agrees with him.

In April, it announced it would implement a new technology curriculum for primary and secondary schools that will teach coding and tech skills.

Kenya has long been known as one of Africa’s biggest tech hubs and is often dubbed the “Silicon Savannah” as many global tech giants have set up here, including Amazon and Google.

Physics matters

Mr Magu’s own passion for computer science was sparked in his teens.

He was doing badly at school, so to motivate him, his father promised to buy him something.

Mr Magu desperately wanted a mountain bike, but in the end, he chose a computer, a bulky early 2000s Compaq.

Playing games on it was a revelation and that night he did not sleep at all.

He decided then aged 13 that he wanted to study computer science at university.

But at school he did not see the connection between studying physics and computer science, so he dropped the subject.

“I almost collapsed as I got the shock of my life that I could not study computer science at university without physics,” he said.

This experience taught him the importance of instilling passion for science and mathematics in children from an early age.

In the end he studied political science, though he spent his spare time learning about electronics – and after he graduated, worked for a Danish tech company in Nairobi as a project associate.

It was during this period that he honed his skills and took part in a pilot schools programme on coding and robotics that inspired him to establish his centre.

Putting local first

The tech scene in Kenya is often associated with foreigners, who operate the majority of start-ups and attract the most financing.

His centre acts as an incubator for local tech-start-ups. These include a digital marketing company in Turkana, a new group that burns waste and uses water hyacinths to make electricity in Kisumu and an artificial intelligence (AI) firm that makes translation apps for deaf people in Nairobi.

Some of them are based at Stem with some of their employees also acting as mentors to the children.

One of these is John, a recent graduate and research engineer – whose name has been changed because of the sensitivity of some of his work.

His family fled conflict in South Sudan and he was born in the Kakuma refugee camp in north-western Kenya.

When he was about five his family moved out of the camp to Nakuru, a city in Kenya’s Rift Valley.

His father could not afford to send him and his sister to university at the same time – so while his sister studied, he managed to convince his father to give him his laptop.

John bought himself a portable dongle and would buy internet packages for about 50 Kenyan shillings ($0.40, £0.35) for 24 hours to get online.

He soon stumbled upon a free online course in computer science offered by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US.

He spent his nights downloading the course and spent his days learning everything from computational thinking and data science to software.

John never had any interaction directly with MIT, nor did he get a certificate, but this course deepened his interest in science and mathematics. When he finally got to university, he studied for a degree in aeronautical engineering.

In early 2021, a classmate of his started to work at the Stem Impact Centre. Intrigued by the work they were doing, he asked the friend to take him there – and eventually ended up doing his work placement there before getting a job with one of its start-ups after graduating.

He is excited about passing on his passion for technology to the young students – and about his ideas that can help tackle issues in rural areas like locust infestations.

Inspired by the success of John and others, Mr Magu is eyeing up opportunities to expand his programme and is currently setting up a pilot in Sudan, with support from a refugee charity that works in the region.

For John, his future ambitions are crystal clear: he wants to study applied mathematics at MIT.