The Other Black Girl walks viewers through black trauma and systemic racism at the workplace. Based on Zakiya Dalila Harris’ novel of the same title, the Hulu show explores the place of femininity and the black woman in corporate America. To what extent, Reviewer Andrew Chatora asks, does one compromise themselves to curry favour with the establishment if only it comes with the material trappings of servile collaboration with the other.

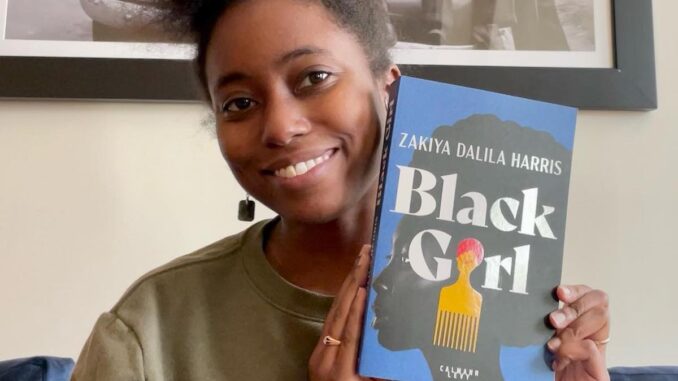

Zakiya Dalila Harris: Photo credit Zakiya Dalila Harris/Facebook Official

Hulu’s new series, The Other Black Girl, follows two black women as they navigate racist micro-aggressions and bullying at their workplace, Wagner Books, a fictional publishing house, while getting to know each other as sisters. The television show is adapted from Zakiya Dalila Harris’ (2021) New York Times bestseller debut novel of the same title. Nella (Sinclair Daniel), the only black editorial assistant at Wagner Books, becomes friends with Hazel (Ashleigh Murray), a new recruit who is also black. The two women come to terms with the challenges of assimilation and racism at the workplace as they are increasingly tangled in a cat-and-mouse dalliance. The quest for sisterhood among black women becomes a central motif of the show as in the book.

Something sits oddly about Hazel, the new girl. She gives off a dark-horse aura of sorts. Her arrival triggers strange dreams and even stranger coincidences for Nella. Hazel is on first-name terms with mystery, for instance, the chilling note directing Nella to “LEAVE WAGNER NOW,” appears to be somehow linked to the former. Perhaps, I resonate more with Nella because I have walked the same road with her. As a non-white teaching English to white kids, I have merited the reproach of some colleagues not because of my inability but because of deeply ingrained racism. Like Nella, the racist micro-aggressions did get to me. But I developed a growth mindset to cope with them away from the victimhood they insistently marked me for.

The quest for sisterhood among black women becomes a central motif of the show as in the book

The Other Black Girl’s diverse media production techniques like eerie music, uncanny-valley grins and flickering lights, the series mirrors the unsettling emotion associated with identifying one’s worth being questioned at the workplace. Throughout the show’s mis-en-scene, props, music score and lighting is a pervasive sense of Misha Green’s Lovecraft Country TV show and Jordan Peele’s directorial feature debut, Get Out. Both texts highlight the insidious nature of racism, how it is meted subliminally to its targets.

The music score is illuminating as it has a fantastic soundtrack crafted by music supervisor Tiffany Anders featuring tracks from Tyler the Creator and Caroline Polacheck that are essential to the story’s themes about complicated friendships and desire. In addition, the series is told from Black women’s perspectives over a sumptuous soundtrack that includes artists like Anita Baker, SZA, TLC and Busta Rhymes, it offers something entirely unique to the genre.

Let’s set the scene with Nella’s days as assistant editor. Before she comes aboard, Wagner is the publisher of her favourite book, written by a black woman, Diana Gordon (Garcelle Beauvais). Diana’s best friend Kendra Rae Phillips (Cassi Maddox) is the first and only black editor at Wagner. Nella is deeply inspired by Gordon’s book, and Kendra Rae’s Phillips’ career is what persuades her to go into publishing in the first place. As assistant editor, though, Nella’s path appears precarious. Wagner Books’ portraits on the wall showcase past editors who are all white males, barring one female black editor, Kendra who mysteriously disappeared in the 1990s. And Kendra’s portrait always seems to be slightly askew. Again, there is clever use of lighting here to signpost viewers that Nella’s chances of upward mobility are structurally throttled.

There is a lot going on by way of latent racism and sexism at Wagner Books. Viewers explore how these wreak havoc on the confidence, dreams and aspirations of the young assistant editor. Injustice is channeled into material for an engrossing series carried on by humour, heart and imaginary twists. The blinding whiteness and lack of opportunity at Wagner Books should not look unfamiliar to anyone who’s worked for a company that sees itself as progressive while upholding decades of racist policy. This is an all too familiar narrative with non-whites working in the supposed first-world diaspora.

Nella’s fractious relationship with her enigmatic black work colleague Hazel torches on an – all too recurring motif in the black community – the crabs-in-a-barrel phenomenon. Black people being disloyal to each other is a theme much highlighted in iconic shows such as Passing (2021) and Dear White People (2014). The Other Black Girl TV show provides a minutiae examination into the toxic work environment within non-Black spaces and show the intimate, yet insidious nature behind a familiar beauty product.

African-American woman with natural hair. Photo: Wiki commons/www.nappy.co/license/)

The metaphor of a black woman’s hair has been an enduring leitmotif in African- American folk history. Zakiya Dalila Harries cleverly uses hair grease in her TV show as a charm to brainwash women into submission, cooperation or assimilated whiteness. This is related to advantages fair-skinned black people got from passing for white in the early aftermath of slavery. Nella Larson’s 1929 classic, Passing, does a profound job of examining this theme as does seminal African American literature texts like The Autobiography of an Ex Coloured Man (1912), Native Son (1940) and Black Boy (1945). Richard Wright, the author of the last two, is renowned for highlighting the psychological effects of racism on black Americans. Through his writing, he underscores the presence of the all-endemic backstory, a systemic causation behind black people’s ‘‘misdemeanours’’ or brushes with the law.

The metaphor of a black woman’s hair has been an enduring leitmotif in African- American folk history

The application of hair grease, the seemingly innocuous cult Hazel is forcibly recruiting, comes with a physical and spiritual reincarnation in which black women pretty much sell their souls to the system as they transform to super- slick well-dressed business elites. A façade of having made, the transformation is reminiscent of the captive black characters in Jordan Peele’s Get Out, auctioned to the highest bidder in a parody modern slave market where black people’s body parts are harvested to meet the medical needs of affluent white people in need of organ transplants. Lovecraft County uses an equally clever method whereby Ruby Baptiste (Wunmi Mosaku), a black woman, has to drink a metamorphosis potion which magically transforms her into a white woman and thereby reap the privilege and benefits of whiteness which she is daily denied in her other real life as a black woman. She even manages to get a job as an associate manager at a place she had earlier been turned away from when she pitched up for a job interview in her black self. She now assumes a new name Hillary under her switching white persona. In Boots Riley’s 2018 film, Sorry to Bother You, black telemarketer Cassius Green (Lakeith Stanfield) soon learns that using a “white voice” is the highway to success. Powerful statements on racial identity politics are made in these films connoting that whiteness is the rite of passage to a desirable life for people of colour.

Black women’s hair has traditionally assumed currency, even in times of slave trade when its elaborate cornrow styles used to surreptitiously map escape routes in South America and hide gold and other valuables to finance the emancipated life ahead. The immense endurance trope of black women’s hair is explored in-depth and with greater nuance in The Other Black Girl.

The Other Black Girl takes satirical shots at the insidious nature of anti-blackness in the corporate world. Nella has to be constantly tiptoeing around her white colleagues and especially fastidious immediate boss Vera Panini (Bellamy Young), the editor who is eventually fired over her refusal to take on board a sensitivity reader’s views. Vera refuses to take on board Nella’s input to call out Wagner’s top author whose representation of black characters in his manuscript is nigh problematic as it is riddled with numerous stereotypes. Ironically, perhaps in another bizarre display of her twisted mind games, it is Hazel, who makes Vera’s faux pa known in Wagner boardroom, resulting in the latter being sacked.

Race politics sits at the heart of this TV show with misogynoir sub-strands abounding. What drives the story is that there’s something strange going on when it comes to Wagner Books and the Black women who have worked for them, and it seems that Nella is going to try to get to the bottom of it. And so the narrative lurches forward to a dramatic finale, making for a perfect cliffhanger as viewers anticipate a possible season 2.

In summing, the show is not just about being black and female in corporate America. The Other Black Girl casts a wider metaphor and awareness on what it entails being black in a predominantly white workplace where parochial white supremacy, misogyny and rampant prejudice still rule in different professional spheres. While Harris deploys racism in the publishing industry as her focal point, I have used the Teaching vocation in my own writing to explore similar issues. Perhaps, what resonates among all of us as writers is not only calling out microaggressions in the workplace but ensuring diversity and inclusiveness thrives as opposed to needless tokenism desired by most employers so they splash on their company websites that they’re meeting diversity quotas.

Author Biography

Andrew Chatora is a noted exponent of the African diaspora novel. Candid, relentlessly engaging and vulnerable, his novels are a polarising affair among social critics and literary aficionados. Chatora’s forthcoming novel, Born Here But Not in My Name, is a long-run treatment of race relations in Britain, featuring the English classroom as a microcosm of wider society post-Brexit. His debut novella, Diaspora Dreams (2021), was the well-received nominee of the National Arts Merit Awards in Zimbabwe, while his subsequent works, Where the Heart Is, Harare Voices and Beyond and Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Stories, has cemented his contribution as a voice of the excluded.